THE GOLDEN RETRIEVER AS A WORKING GUNDOG

Graham Cox looks at what makes Goldens distinctive

Robert Atkinson with the 1982 Retriever Champion FT Ch Little Marston Chorus of Holway

The competitive record of the labrador doesn’t simply speak for itself. It shouts and stamps its feet. Nor is the record a matter of recent provenance. Once the labrador came seriously onto the scene the speed with which, colossus like, it came to bestride the world of working retrievers, was nothing short of remarkable. The first trial for retrievers in 1899, won by the Flatcoated Retriever ‘Painter’ was in fact a mixed stake with two Clumbers, one Irish Spaniel and one Field Spaniel competing alongside a Curly Coated retriever and five Flatcoats. So there was no labrador represented. A decade and more on, in the last full season before the Great War, some 14 field trial meetings were held and, of the 247 dogs which entered, no fewer than 179 were labradors. Succeeding years simply accentuated the pattern as curly coats departed the competitive scene and flatcoats receded.

The competitive record of the labrador doesn’t simply speak for itself. It shouts and stamps its feet. Nor is the record a matter of recent provenance. Once the labrador came seriously onto the scene the speed with which, colossus like, it came to bestride the world of working retrievers, was nothing short of remarkable. The first trial for retrievers in 1899, won by the Flatcoated Retriever ‘Painter’ was in fact a mixed stake with two Clumbers, one Irish Spaniel and one Field Spaniel competing alongside a Curly Coated retriever and five Flatcoats. So there was no labrador represented. A decade and more on, in the last full season before the Great War, some 14 field trial meetings were held and, of the 247 dogs which entered, no fewer than 179 were labradors. Succeeding years simply accentuated the pattern as curly coats departed the competitive scene and flatcoats receded.

Golden Retrievers were initially registered as flatcoats and defined, at that stage, only by colour. Registered by the Kennel Club as a separate variety under the title ‘Golden or Yellow Retrievers’ in 1911, the following year saw the breed secure its first field trial award when Capt. H.F.H. Hardy took second place in the Gamekeepers’ National Association Open Stakes at Netherby. In more recent years only Golden Retrievers have managed, on occasion, to mount a serious challenge to labrador dominance at the highest levels of competition. Just three times during the post-war period has a golden won the international Gundog League’s Retriever Championship. In each of the other 51 years the name of a labrador – invariably a black labrador – has been inscribed on the Glen Kidston Challenge Cup.

So the public record overwhelmingly endorses the assessment offered by Colonel Hawker when, in 1830, he found himself lamenting the dearth of the dogs he considered ‘by far the best for any kind of shooting’. It wasn’t until the last decade of that century that the name labrador became common usage, but enthusiasts would soon have no doubt that Hawker’s extravagant claim that the breed was ‘without living equal in the canine race’ had been substantially vindicated.

Other breeds, of course, had their committed advocates. One hundred years on from Hawker’s paean to the labrador, Captain Hardy published his book Good Gun Dogs and in it he explained why he had kept goldens for more years than any other breed of gun dog. It was not just a matter of sentiment. “I do like them best of all”, he emphasised: but he accounted for that liking in very practical terms. “I find them easy to train and to manage, good trackers of wounded game, and excellent at water work.”

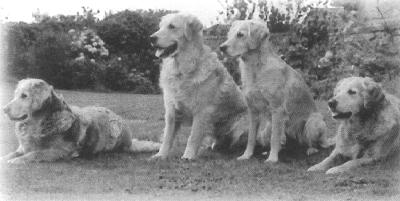

Left to Right; FT Champions Holway Jollity; Holway Chanter; Holway Gem; and Holway Gaiety

At little later the Rev. E.N. Needham-Davies, contributing a chapter on the breed to a book entitled Gun Dogs; Their Training, Working & Management and conscious that his article would be read in a comparative sense with the articles on other varieties of the retriever family, drew attention to similar qualities. Being a younger breed the Goldens, he felt, had not been crossed as had happened with some other varieties. So, whereas some Field Trial work showed dogs to be very reliant on the whistle the Golden had not lost his ancestors’ hunting traits. “Fast and sure”, he wrote, “is excellent, they are two gundog virtues but the greater of these is sureness. The Golden, broadly speaking, is sure”. with “a nose second to none, he holds his line and carries it”. Too much pace, he added, and he may drop it.

“Tiptop” as water-dogs, they could also generally be relied upon to be bold in cover: though he was careful to add that generalities can be dangerous. Where he was unequivocal was in extolling the virtue of what we would now call biddability. The Golden, he said, “is a nice dog to teach. He is kind and willing to learn”, adding “I would say that he was on the whole easier to break than the other varieties”. This from a man who “had, bred, trained and used Curlies, Flats and Labradors.”

Generalities are, indeed, problematic. Even this one, So, although we may restrict our attention to working bred dogs we soon become aware that the force of different bloodlines may be such that variations within the breeds can be as significant as differences between them. As ever there is no substitute for knowing your stock and moderating the training process accordingly. But there certainly are popular suppositions about goldens and the most prevalent is the truism that goldens are slower to develop than labradors: puppyish and playful for longer with everything which that implies for progress.

FT Ch Treunair Cala

As a generalisation that is on track, but it doesn’t say enough. What matters is that temperament develops more slowly than raw intelligence. You have, therefore, to resist the temptation to race ahead: a temptation which is ever present because of the speed which working goldens typically learn things. More to the point, I think, is a less generally acknowledged characteristic which is every bit as relevant to the strategy you adopt. The shortest way of expressing it is via June Atkinson’s warning “you must never lose your temper with a golden” and the best way of elaborating the point is to draw on the wisdom of the man who, for over thirty years, was responsible for the breeding, rearing and training programmes of the Guide Dogs For The Blind Association. Derek Freeman’s Barking Up The Right Tree published in 1991 presents fascinating insights from an organisation which has had its best success rates with Golden Retriever and Labrador first-crosses. Of goldens he writes that willingness sometimes dries up and that this used to be termed ‘stubbornness’. That isn’t, he says, a fair description. “A better term is ‘lack of generosity’. Golden Retrievers are intelligent, they know what life is about and as individuals soon get to know what they can get away with. It is a breed which is easily offended and when their generosity or willingness is withdrawn, it can sometimes be difficult to restore”.

Daphne Philpott receiving a Diploma of Merit from Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II Gained at the 1987 Retriever Championship with Abnalls Evita of Standerwick, whose dam Standerwick Roberta of Abnalls was also running.

Daphne Philpott receiving a Diploma of Merit from Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II Gained at the 1987 Retriever Championship with Abnalls Evita of Standerwick, whose dam Standerwick Roberta of Abnalls was also running.

That is incredibly perceptive. Goldens need to have their sensitivity respected and they assuredly do not need to have their intelligence patronised by people confusing a different pace of maturing with innate ability. Those are two very different things even if you can only realise the potential of the one by taking full account of the other. Appreciate these points and much else falls into place. Goldens are gregarious and take less readily to kennel regimes. Above all they relate. They want to be with humans. It is possible to let goldens be ‘wild’ as puppies and still get them back ‘in hand’. By contrast, and this is the assessment I have heard from massively experienced and successful trainers, you would in all probability lose a labrador if you let it go. A labrador is more than happy to be independent whereas the golden wishes to be with a human. It is always dangerous to treat the best cases as if they were the generality, but there are guns who have ‘lost’ labradors and had it suggested that they try a golden and it works.

By the same token these considerations, taken together, go a long way to accounting for the fact that when it comes to labrador enthusiasts fancying ‘having a go’ at training a golden it seems to be a case of ‘many are called but few are chosen’. Janet Webb and Nigel Mann come to mind, but then one struggles. Keith Erlandson’s first trial bred dog was a golden who proved, by his account, ‘unbelievably easy’ to train and in his assessment of the breed a quarter century ago he wrote “A good golden is second to none and at the risk of sounding controversial I believe a top specimen can actually be superior to the very best Labrador but I will admit that such dogs are very thin on the ground.” It would be hard to avoid going along with that assessment: though as of now one would have to concede that at the very highest levels of field trial competition ‘very thin’ is looking even thinner.

Working goldens are an important part of a very broadly based pyramid of working gundogs who make their contribution to the sport of shooting in ways too numerous to spell out. Field trial competition is, or should be, normal work in the field carried to a higher state of perfection. Trials dogs are at the apex of that broadly based pyramid because trials constitute the only public and accountable examination of the quality of a dog’s work. At the very highest level, the IGL Championship, the minimal golden presence has not enjoyed any distinction of late and it is now almost two decades since the most recent of the breed’s three victories was achieved.

Daphne Philpott accepts a retrieve from Abnalls Evita of Standerwick, watched by Judge (on left) Roy Taylor of Ardyle fame, in the 1987 Retriever Championship on the Sandringham Estate

Daphne Philpott accepts a retrieve from Abnalls Evita of Standerwick, watched by Judge (on left) Roy Taylor of Ardyle fame, in the 1987 Retriever Championship on the Sandringham Estate

It would be quite wrong to draw pessimistic conclusions however. Look at less exalted levels of competition and the picture is one of commitment and enthusiasm. Participation rates can often tell us more than success rates which, for all kinds of reasons, can be more variable. Over the past three seasons the number of Goldens running in Open. All Aged and Novice stakes have remained broadly consistent, with the 1997-8 season clearly the most successful in that eight Open wins were almost matched by seven in All Aged Stakes and five Novice wins were also recorded.

A fuller account of the working record of the breed, with particular attention to the dogs who achieved their working titles, can be found in the books of Champions, the fourth one of which covering the period 1996-1999 was published recently. Volume one, which covered the period from 1946 to 1985 is now something of a collector’s item, but Volumes two, covering 1915-1939 and 1986-1990, and three dealing with the years 1991-1995 and, of course, the most recent, are still readily available. In 1994, meanwhile, Albert Titterington and Michael Gaffney published The Golden Retriever in Ireland which deals comprehensively with the working side of the breed in the Republic and in Northern Ireland.

Good goldens may be harder to find than amongst the more numerous retriever breeds, but the testimony of those who have enjoyed success with them proves time and time again that when they are good they have something special about them. If good goldens are like gold-dust, perhaps that’s only to be expected. What is for certain is that to achieve success with them you have to have a feel for what makes the breed distinctive. Develop is effectively and the response can be absolutely splendid. GRAHAM COX

50 Years of Trialling Excellence

No anniversary could be more apt, says GRAHAM COX, than the one June Atkinson is in the midst of celebrating

It was the Barrister who first caught my attention. Not some be-wigged denizen of the Inns of Court. No, it was THE Barrister. A dog whose burnished athleticism and gamefinding confidence seemed to carry all before it, and whose joy in his work was compelling. Anyone seeking a working definition of charisma needed to look no further. The name, meanwhile, proclaimed an authority which performance invariably confirmed. In one sense though the ‘playing dogs’ image is in danger of. But if I think of the names of Holway golden retriever field trial champions which best convey the image I have of these dogs at their best three spring immediately to mind. Zest certainly: but, before any others, Jollity and Gaiety. For those names capture better than any others the quality which Game Fair crowds, for instance, have always appreciated. These are dogs which are happy in their work.

Typically, June Atkinson talks not of ‘training’ but of ‘playing’ dogs and it seemed only appropriate that she should move to a cottage called Merryfield shortly after her son Robert took over the running of Holway’s 820 acres in 1976. Set in the heart of the Cattistock country, June ensured during her years of stewardship, after the death of her husband Martin in 1968, that the concern to avoid the worst excesses of post-war agricultural intensification was sustained and the farm’s water meadows, ancient woodlands and mixed cropping with livestock remained a splendid gundog playground. Far from the madding motorways, Dorset is one of those counties you can’t cross into without feeling that life has changed for the better and June Atkinson is very much the place. masking a no less vital truth. As kind as she is tough, June Atkinson brings to her sport a fierce competitiveness and combines it with a marked reluctance to suffer fools, whether canine or human, either gladly or at all. You don’t put together the sort of record which she has achieved over fifty years without massive commitment and talent to match. Indeed, for many years the latter was considered almost mystical and it used popularly to be supposed that only June Atkinson could handle Holway dogs. Not so. But what is certain is that she has the most remarkable ability with dogs – and horses for that matter – and that a formidable physical presence goes some way to accounting for it. Only some way though, for it is the understanding borne of years of experience and the tone of voice which more than anything secures the rapt attention of the dogs which are synonymous with her name. Whatever charisma is, the dogs patently think she has it in spades.

“Go anywhere in England”, the playwright George Bernard Shaw once wrote, “where there are natural, wholesome, contented and really nice English people: and what do you find? That the stables are the real centre of the household.” Well, there can be little doubt that he would have found Holway congenial. Turn from the Yeovil – Dorchester road and wind towards Cattistock through the high hedged lanes, freckled in the summer months with the carmine pinks of campion and foxglove, and soon, as the road bends, a small sign directs you into the farm drive. You pass horses and sheep grazing on the right; to the left a magnolia blooms by the kitchen garden wall; and there is a horse let into the iron work of the main gate. Park by the horse box and in no time at all – and it is the same whether you are at Holway or Merryfied – your car will be surrounded by an inquisitive pack of goldens of every age eagerly heralding your arrival.

There are stables, to be sure, but no kennels. And as you realise that moments before the dogs were stretched out by the Aga or curled up in an old suitcase in the kitchen, or perhaps lying in the back of June’s car you begin to appreciate that the system at Holway seems to fly in the face of many of the cherished rules to be found in typical gundog training manuals.

Indeed, it would be hard to find anyone less cluttered by preconceptions or theories than June Atkinson and it is hardly surprising after so many years that the process of training a dog seems a self evident one to her. How many years? There can sometimes be an arbitrariness about anniversaries depending on when you start counting. This year, however, neatly avoids the dilemma: sandwiched, as it is, fifty years on from the year when June acquired her foundation bitch and the year in which she won her first field trial award. But 1947 was also the year in which her original mare Miss Muffet was bought as a yearling from a dealer in Sussex. There have, since then, been 65 home bred point-to-point wins from descendants of Miss Muppet, 53 of them ridden to victory by Robert and in equine and hunting circles the names Brown Spider, Express Spider and Baroness Spider enjoy a resonance akin to that of the Holway goldens. The racing interest is crucial, because until the point-to-points are over June does not even think of dog training and so, without it being a matter of conscious resolve, she avoids the temptation – to which so many succumb because they are more than capable- to push young dogs on too fast.

In 1947 Britain at last began to feel the war was over. Denis Compton scored 18 centuries that summer, and there were lock-outs at Lords and Headingley. England went sport mad. The first Edinburgh Festival was held and the Land Rover, symbol of dependability, was born. And June Atkinson acquired Musickmaker of Yeo, a foundation bitch who gained her working title after failing to impress early on. We can surely all take heart from the story behind the phrase ‘Lot 10’ which is scribbled on the top right hand corner of Musick’s pedigree. June had seemingly felt that she was not making much progress and had placed her in a sale at the Dorchester Fair which used to be held in those days. But, typically, she could not go through with the sale and withdrew the bitch who was to begin a remarkable sequence of results.

To date June and her son Robert have achieved twenty times over what most gundog handlers dream of doing once: and that understates the achievement because many of her dogs have won enough Open stakes to become Field Trial Champions many times over. It is a record of amazing consistency, achieved with a breed which matures rather less quickly than Labradors or springers. Add the names of the nine Holway dogs made up by others both here and in Europe and America and the roll of honour is a long one. FTChs Musickmaker of Yeo, Mazurka of Wynford who won the Retriever Championship in 1954 when it was held over three days at Six Mile Bottom and Shadwell Park and was second the following year at Sandringham, Holway Flush of Yeo, Holway Lancer, Holway Bonnie, Holway Zest, Holway Westhyde Zeus, Holway Gaiety, Holway Barrister, Holway Jollity, Holway Chanter, Holway Gem, Holway Dollar, Holway Grettle, Holway Ruby, Holway Trumpet, Holway Corbiere the swashbuckling ‘Desert Orchid’ of the gundog world, Holway Crosa, Holway Eppie and Holway Quilla who, with an unparalleled sense of occasion in 1995 won the first Open Stake which the Golden Retriever Club was able to hold after a period of enforced de-registration.

Asking June to name the best is to ask the impossible. Dogs, no less than humans and horses, are individuals and she has no preference for dogs or bitches. Mazurka was the first golden to win the Rank Routledge trophy in 1957 but it is one of his last offspring who took it in 1970 and again in 1971 that has a special place in June’s Holway pantheon. FTCh Holway Gaiety, out of FTCh Holway Flush of Yeo who was the dam of five English, one American and one Belgian FTChs, won a staggering eight Open Stakes. Possessed of a wonderful nose and absolutely fearless in the thickest cover, she was a delight to handle: epitomising the combination of biddability and gamefinding that June looks for before all else. That powerful bitch line is the golden thread that runs through the Holway tapestry That unswerving appreciation of priorities and determination to accept only the highest standards is wedded to a delightfully uncomplicated approach which has only one rule at its heart. With young dogs, says June, “only give a command if you are in a position to make sure it is carried out.” Needless to say the sheer magnetism which makes such simplicity possible is not so easy to put into words.

June has judged the Retriever Championship no fewer than six times and, over a period which has seen the sports of shooting and trialling transformed, has sustained her commitment to a fiercely competitive yet Corinthian ethos. The achievement has been truly remarkable and nothing has been more perennially irritating than hearing her described as ‘the leading Lady handler’. No sexist qualification has ever been so utterly unnecessary.

Graham Cox – This article first appeared in The Shooting Gazette, Issue 83, Sept 1998

The Happy Half Century was celebrated at a dinner on the middle night of the GRC 2 Day Open Stake at Sandringham in November 1999, where June was presented with a Blackthorn and horn stick with a solid gold oval inset into the top of the shaft, engraved with her initials.

Left is a photograph which will become a collectors item.

These are the 3 owners of the post-war Golden Retriever winners of the I.G.L Retriever Championship.

Right to Left:

Mrs Jean Lumsden (nee Train) 1952 FT Ch Treunair Cala

Mrs June Atkinson 1954 FT Ch Mazurka of Wynford

Mr Robert Atkinson 1982 FT Ch Little Marston Chorus of Holway.

Making, Not Finding

A tribute by Graham Cox to his Ft Ch Littlemarston Comma of Wydcombe

My golden FT Ch Littlemarston Comma of Wydcombe was whelped on August 26 1984, gained her title on January 9 1990 and died on June 3 1997. Active and thrilled to be included in any training activities right to the end she did not long the survive deep surgery which failed to get to the root of the problem which first been similarly operated on in January. Though she must have been in massive discomfort she, not for the first time, had given no hint of a problem, the seriousness of which shocked the vet when he investigated. Always readily cooperative, the practice considered her its easiest patient. We simply had forever to guard against supposing her sound when she was in fact carrying some ailment or injury. We did not always succeed.

My golden FT Ch Littlemarston Comma of Wydcombe was whelped on August 26 1984, gained her title on January 9 1990 and died on June 3 1997. Active and thrilled to be included in any training activities right to the end she did not long the survive deep surgery which failed to get to the root of the problem which first been similarly operated on in January. Though she must have been in massive discomfort she, not for the first time, had given no hint of a problem, the seriousness of which shocked the vet when he investigated. Always readily cooperative, the practice considered her its easiest patient. We simply had forever to guard against supposing her sound when she was in fact carrying some ailment or injury. We did not always succeed.

Making, not finding is my title for this piece because her career exemplifies a point whose importance can’t be over emphasised. When it comes to strategy with dogs there are those who seem to think they will be able to find what they are looking for. They seem to achieve a remarkable turnover of dogs and, since sentiment often decrees that some are kept, quickly become over dogged. The alternative approach concentrates on doing whatever is necessary to make something of what you have, recognising that all dogs are individuals and that each will need some training particular to it. Of course in practice it’s not quite such an either or matter: but the point is worth making that way because the difference in underlying philosophy is fundamental.

Patience matters and, as the late Eric Baldwin used to remark, “there’s many a dog ruined before it’s four”. Similarly Bob Baldwin, three times a winner of the Retriever Championship, used to counsel against running dogs in trials in their season and was wary about giving them experience on runners until they were really mature. Making haste slowly was a precept I had in mind when I acquired Comma and it was underlined by her breeder Michael Dare’s comment to me when she was still quite young that it hadn’t really come together with her dam’ FTCh Holway Calla, until she was three.

Calla was the main reason I had been so keen on the puppy. She had been regularly shot over and, though never extensively trailed, had won three open stakes in successive seasons, suggesting a sound temperament to go with her uncanny sense of where the game might be. At the conclusion of one of those wins I saw her twice immediately pick a bird from a copse after the other final round dogs had worked long and hard for their finds. A seemingly innate ability to put herself right in relation to the work she had to do never deserted her. Game finding is what really matters and on that score she had real quality.

She had been put to FTCh Holway Trumpet and since I had his little sister Holway Cymbal of Wydcombe I felt I had a good sense of what to expect from the mating. As well as three seconds in open stakes she was an incredibly reliable test performer with a good few prestigious wins to her credit. Imagine, then, how disconcerting it was to find myself, in Comma, with a young dog who quite simply seemed to lack the fire that, more than anything, I associate with the Holway goldens.

The training diary speaks plainly of my impressions. Time and time again I am writing that ‘she never looks at all exciting’ though I concede that Comma – named after the butterfly rather than the punctuation mark – does do things very efficiently. She marks well, mostly puts herself right for the wind and invariably stays in the area of the fall. Reading through those pages and pages of entries the word I keep finding myself using to characterise her work is ‘sensible’, a quality which- though admirable – would, I felt, be unlikely to catch the eye of a judge.

What Comma seem to lack was drive. She was a charming and undemanding dog about the house. There was none of that pushy nosing of one’s arm when seeking attention: instead she would sit politely alongside and offer a paw. Endearing as such self-effacing mannerliness undoubtedly was, the diary brutally records my doubts about the quality as applied to work. With Comma twenty-six months old the carefully considered phrase ‘hopeless prospect’ appears after one particularly uninspiring session.

But drive alone is no virtue. Indeed, Vincent Routledge, in my favourite gundog book, The Ideal Retriever and How to Handle Him, is careful to distinguish drive and determination when setting out the primary qualities required in a retriever. Dogs with determination will ‘go on hunting until call up’ and will ‘nearly always face punishing cover when required’, he writes, whereas drive is ‘all to often applied to a dog which hunts wildly and wide, never marking good the ground as he goes.’ Before determination, though, Routledge put nose and brains. And on those criteria Comma was as impressive as she was disappointing on the speed stakes.

I had determined early on that there was little point in running her in working tests which would surely highlighted her shortcomings without providing an opportunity to display her better qualities. And though I, perhaps, under-valued them at the outset they were very real. They were what I had to work on. For she would always show a more than usual readiness to adjust her pace to suit scenting conditions and an ability to hold the merest touch of scent. She came into her own on game and became reliable on runners. With some relief I came to see that a dog which I had almost discounted and whose career was, in some respects, unconventional nonetheless had prospects. In the event she put together a creditable trial record which, amongst other awards, included three any variety open stake wins: the first of them a 24 dog stake, which she won with impeccable marking and eyewipes, made possible by acute nosework. In the trial which made her up she did her best work third dog down on birds that were never found, owning lines that others had been unable to acknowledge and trying desperately to make something of them. Her performance in an invitation test at Sandringham some months later prompted one of the judges, the late Cicely McMullen, to sympathise with Comma who seemed to her to be working under sufferance.

She was. There never was any point involving her with working tests. Gamefinding was a different story though. And together with her unfailing equanimity it made her a marvellous dog to shoot over. Most shooting dogs become sweet old things in time. Comma always was. She may not have been a dog to make the hairs on your neck stand on end, but she was utterly well mannered and totally sound. She never anything nor made a sound whilst working. A thoroughly good sort in fact.

Marilyn, my wife, who had championed Comma’s qualities whilst I was still dwelling on her shortcomings, tearfully eulogised her as someone ‘who spoke to everyone and made no demands: a very important person’. I could only agree. You really miss a dog like that.

Graham Cox – This article first appeared in The Shooting Gazette, Issue 73,Nov 1997